LLMs need skilled human partners

I stumbled across this Jacobin article responding to Chris Hayes’ tweet where he says “the unified class project of billionaires right now is to do to white collar workers what globalization and neoliberalism did to blue collar workers.” The article pushes back against that narrative, mostly from a structural standpoint—there is no need for a concerted class war effort on behalf of the ultra-rich, because the normal machinery of capitalism will do the job just fine.

The stories about mass layoffs at tech firms, coupled with Donald Trump and the New Right’s attacks against “credentialed elites,” feel like evidence of something both seismic and systemic. But the idea that tech billionaires and elites are engaged in a full-scale campaign specifically against white-collar workers misses a deeper, more uncomfortable truth: What we’re witnessing isn’t some coordinated political vendetta against the laptop class. It’s just capitalism working exactly as intended.

I agree with this. Back in 2019, when labor power inside Big Tech felt ascendent, I commented on an internal post at Meta that we (as in, software engineers) would, when it’s over, regret not using this moment of relative strength to organize and form unions. I was pilloried because Silicon Valley is, perhaps like nowhere else in America, filled with temporarily embarrassed billionaires, but I think the last few years have shown my position to have some merit.

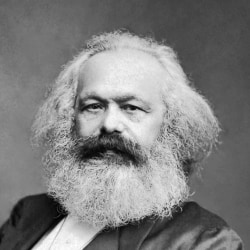

However, what caught my eye was a quote the article attributes to Marx’s Capital. It’s actually from Gabriel Deville’s 1883 The People’s Marx, a popular abridgement of Capital, but the idea is faithfully rendered:

The constant aim of these improvements is to diminish the manual labor for a given capital, which, thanks to these improvements, not only requires fewer laborers, but also constantly substitutes the less skilled for the more skilled.

For the current generation of LLMs, for coding at least, the situation is the opposite—they require fewer engineers, perhaps, but only skilled engineers can get the most out of them. Getting production-quality work out of an LLM requires constant vigilance from someone experienced enough to redirect the machine out of blind alleys. The context window of a staff engineer is huge, and her head is filled with heuristics that were built out of experience that is not latent in the training data these models consume.

This might not last forever. The centaur phase for software engineering might be quite short. But for now, at least, it is genuinely symbiotic: the engineer increasingly relies on the LLM’s speed and breadth, while the LLM relies on the human’s hard-won experience and real-world context. The best outcomes I’ve seen come from people who understand the machine enough to coax excellent work out of it rather than riding it off the vibe-coding cliff.